|

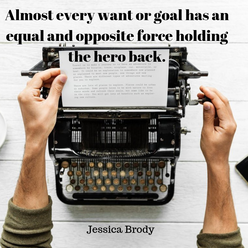

My mother quoted both Shakespeare and Newton and others I have yet to divine, and as a child, I was completely unaware. It's completely shocking to read a work of great literature, or science, and hear my mother speaking the lines from decades past. When it came to Newton's laws, her recitation tended to follow a complete kid klutz moment. For instance, putting books onto the dining table, push back, spill milk across the dining table. Mom would spout Newton's 3rd law: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. I guess that was better than yelling at us for spilled milk. But here's the thing. Newton's laws apply to people and characters as well as the universe. Newton's law of inertia, states that an object at rest will remain at rest unless acted upon by an outside source. In this example, the object at rest is our character before the story begins. Jennifer Brody, in Save the Cat! Writes a Novel, writes: [momentary pause wherein I acknowledge my mother's genius] In this analogy, the character is the object at rest. The character is living their happy or unhappy life in stasis, or as Christopher Vogler (The Writer's Journey) calls it, the Ordinary World. The character may be unhappy, but they're not unhappy enough to move. Take Luke from the original Star Wars. He's completely unhappy working for his uncle on the farm at the far end of the universe, but he's there anyway, plugging along, dreaming about leaving, "some day." He has the desire, but not the actionable force. It takes a droid, a crazy old hermit, and the death of his aunt and uncle to "force" him from his Ordinary World. Vogler called this the Call to Adventure, but in Brody's version, the events that take place are the equal and opposite force that compel the object at rest into an object in motion (or, a Character in Motion). Once the character is in motion, their wants and goals keep the plot moving. When a hero wants something, it sets them in motion. It gets them off their butt and into the action (Brody 13).  As the story progress, the equal and opposite force that Brody discusses can come to life through either conflict or a nemesis (antagonist). It is the equal and opposite force that acts against the character in motion. It's the question "[w]hat is standing in the hero's way?" The force standing in the hero's way must be strong enough to push him off course. For instance, think about what it took to force the Millennium Falcon close enough to the Death Star to get captured? And yet, isn't that where Luke and Han were destined to go? Think about your current work in progress (WIP).

I never stopped to consider that something in science, one of my least favorite subjects, could impact my writing world. That was a deficit in my viewpoint. Everything in the world and on our planet can impact our writing world. From years ago, my mother was teaching me how to apply universal laws to my life, and I am the better for it. Now, if I could just find that outside force to get the rest of my life in motion.

0 Comments

As a general rule, and of course there are exceptions, writers are introverts, but even extraverts acknowledge that writing is a solitary act. It's easy to get stuck in our heads and in our stories rather than live in the real world. It seems easier, I think, because our families--no matter how supportive--don't really get writers. Last semester in one of my undergrad creative writing classes, I asked the students why they write. A young lady, about sixteen (we have dual enrolled high school students on our campus) with long hair and thick glasses spoke up. She's rather shy, and this may be the most she spoke in class. She said, "I write to shut up the voices in my head." Immediately several people nodded in agreement. When I told this story in a faculty meeting, several of my colleagues looked at me like I'd lost my mind, some suggesting that maybe it was time to refer the student to behavioral intervention, because they really don't get it. If our families struggle with understanding our writing world, the people in the math department really don't understand creativity. So we go to writing groups, develop writing communities, and eventually go to a writer's conference, because the only people who understand writers are other writers. Once or twice a year, we need to step out of our writing cave and visit with the only people on the planet who do understand. Writing conferences have personalities just like people. If you go to the ThrillerFest, you'll be surrounded by thriller writers and will likely have workshops on law enforcement procedures, autopsies, and forensics. Mystery writers surround themselves with stuff of mystery, romance writers talk relationship building and romance tropes, while YA authors talk about everything. A general writing conference might have tracks for fiction writers, poets, and another for creative nonfiction. There might be someone who talks about memoir and another who talks travel writing. So when you pick a writing conference to go to, make sure that they're your people. For instance, writing poetry is not my jam. SO if I ended up in a poetry-writing conference, I would be out of my element, which is the exact opposite of what we want in a writing conference. So do your homework and make sure the conference covers the topics that are of interest to you and your genre. Once you sign up, or as you're signing up, you'll have to answer questions about food choices (yes, most conferences support vegan or gluten-free eating), but then it gets down to the nitty-gritty. Do you want an agent or editor appointment? Who with? Spend some time researching the agents/editors who will be there so you know which is most likely to appreciate your book. For an editor pitch, this is a great way to get past the slush pile to submit directly to an editor. Make sure, however, that you've checked to see if they accept un-agented work/writers. Do your research and know what they publish, what lines they have, and what their current submission guidelines are. For instance, at dinner during the conference last weekend, a writer at my table said the editor she pitched to was really nice and helpful, but "she doesn't edit horror." While the editor did make some recommendations for next steps for this writer, the writer should have known going into the conference that this editor wasn't an editor for a horror line. That's basic research that would have given the writer better options for her one pitch appointment. If you're considering an agent appointment, figure out why you want an agent. There are oh so many reasons, but here are some from "How to Find a Literary Agent:"

If you're looking to pitch to an agent, here are some things to consider as you pick who you want to pitch to:

One of the interesting things I've noticed the last couple writing conferences is how my attitude and expectations from the conference have changed over time. When I first started going, I was all about the workshops, spending hour after hour in a clogged hotel conference room absorbing information, but as I've progressed in my career, those workshops hold less appeal. Of course there are exceptions. The two hour workshop presented by a coroner talking about dead bodies (DB) and the kinds of evidence we can retrieve from the body was the most amazing workshop I've ever attended, but typically, the workshops are things I've worked on through my coursework and my reading, and now I'm looking to focus on publishers or agents, so I know who the industry players are. Which leads to the next reason every writer should go to conference: to network. Yes, dear introverted writers, I know this sounds like hell. For some of us, networking is worse than hell, but we need to know who works for which publisher. Did they move, did they change to a different line, did they become agents or move to Hollywood? These are the kinds of details you really only get by becoming involved in a writing community and going to a writer's conference. Last summer I attended RWA's conference because it was in Denver, so I didn't have to pay for travel expenses, which makes many national conferences an expensive proposition. Before my kids were born, I had been highly involved with RWA, even acting as president for my local RWA chapter, and I went to conference every year. I absorbed the workshop materials, enjoyed hanging out with my friends at the bar (every writer's conference ends up in the bar), but I didn't do an agent or editor pitch because I wasn't ready for it.

But when I went to RWA last year, I wasn't interested in the workshops (except the autopsy one and another on self-defense for writers), because I was there to make industry contacts. A good friend of mine, who has been even more actively involved than myself, took it upon herself to help me network. I didn't realize this until halfway through conference when I legit hadn't attended a single workshop... But she had me at lunch with one group of writers, drinks with another, and after hours with yet another group. She hosted a tarot reading so I would get to know yet another group of writers all in much more advanced stages of their careers than myself. She was like a publicist who was getting my name out there and connecting me to industry professionals. It was a fabulous (and exhausting) conference. When to go to a writer's conference is a personal and financial decision, but when you do take the plunge, know why you're going and what you want to get out of it. This last conference at Pikes Peak Writers, I had two goals. First I wanted to grow my writer's resume by building a reputation as a presenter and speaker. This worked out well for me and has led to another conference gig this fall at Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers. Second, I wanted to pitch to an agent. My publisher didn't require an agent (some do), and since I had researched my publisher's contract terms before signing with them, I didn't *need* an agent, but now I'm at a crossroads with my career. I have 6 books and a novella out in the world, and I really want an agent to take some of the business stress off my shoulders so I can focus on writing. Because I knew my book, my goals, and my pitch so well, the agent asked for the proposal within two minutes of me walking into the pitch room. That gave me the last eight minutes to simply have a conversation and decide if I think this is the person (or the kind of person) that I want representing my work. Writer's Conferences are amazing opportunities for writers at all stages of the writing career. They build your writing skills, your industry knowledge, and your networking options. The only question left to ask is when are you signing up for your first conference? First, a confession...When I first started writing, a decade or two (ouch!) before I actually published, I wanted to be a historical romance writer. My favorite stories to read were Regencies and, because I read them, I wanted to write them.

Enter reality. Historical romance in general, and Regency in particular, has very demanding fans. Get something wrong about the Regency era, and the readers WILL haunt you. And, as much as I loved to read them, I really didn't want to do that kind of research. Years later, I worked in the public library system in the reference department (yes, I see the irony). And I really do love research now, but I no longer want to write Regency. :) I learned a few things in the process, though.

Most of it is fun. Often it is distracting from the real work, but necessary all the same.

The best advice I can give, however, is to enjoy the ride. Research can and should be mentally engaging. It should be interesting and intriguing. Consider it playtime. Have fun! Years ago, as a new single mom, I got a job working in the optical department at Wal-Mart. First off, that’s a really weird and unexpected place to find a writer, and second, it wasn’t exactly in my career plan, but I needed a job, and Wal-Mart was hiring. We had to go through a week of classes and group discussions with other new hires back in the HR section. One discussion asked us to introduce ourselves and say why we wanted to work at Wal-Mart. Note the phrasing: wanted. Along the way, we each told socially acceptable lies about why we wanted (not needed) to work at the big box store in the sky. One young man, with messy dark hair and sad eyes, broke the mold, however. He looked around the table at the eight of us sitting there, and said, “I graduated from college… and then… life didn’t go as planned.” Truer words, my friend. That moment when life doesn't go as planned? That's conflict Conflict “arises because something is not going as expected” (Kress 13). Conflict belongs in the early part of your story, so readers want to know what happens next. If nothing happens, if life goes as planned, where’s the conflict? Where’s the interest? “But no matter what kind of conflict your story explores, its nature should be hinted at in your opening, even though the development of the conflict won’t occur until later” (Kress 13). Let’s take a look at my favorite Harry Potter. There is an implied conflict from the outset as Professor McGonagall, who we don’t know much about yet, says that the Dursleys are the “worst sort of Muggles” in the movie version, and that you “couldn’t find two people who are less like us” (Rowling 13) in the book. Readers see the conflict developing within the first chapter, and that conflict between Harry and the Dursleys goes until the last book in the series. Along with that conflict, the larger conflict with Voldemort is implied here as well. McGonagall mentions that the only one Voldemort is afraid of is Dumbledore. She relates that Harry’s parents have been killed, by Voldemort, and somehow, a baby—Harry—survived. He was the boy that lived. As writers, we need to establish that conflict early so the reader wants to stick with our story. We don’t always know—going in—the various layers of conflict within our story, so once we finish the draft, we need to evaluate the level of conflict and where it begins. The novel I’m working on now is a straight fiction novel (as opposed to romantic suspense). The first time through, in the original draft, I wrote quickly and recognized some of the conflicts right away, but it wasn’t until I finished the novel that I recognized the conflict that wound from the beginning to the end. On the rewrite, I’m adding in hints of this conflict throughout, including the first chapter, so I can ensure the conflict is enough to sustain the reader. Looking back at our Harry Potter book, we see conflict in the first paragraph: “Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say they were perfectly normal, thank you very much. They were the last people you’d expect to be involved in anything strange or mysterious, because they just didn’t hold with such nonsense” (Rowling 1). The implied promise here is a conflict between the Dursley’s expectation of “perfectly normal” and the “strange” and “mysterious.” For your own writing:

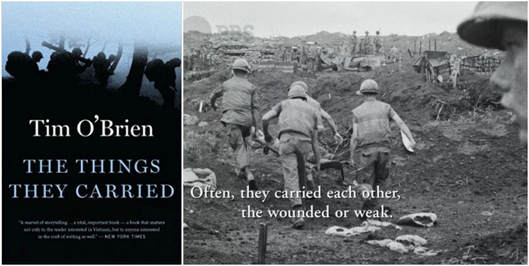

Kress, Nancy. Elements of Fiction Writing – Beginnings, Middles, & Ends. Writer’s Digest Books, 2011. Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Scholastic Press, 1997.  If we read much or often, and if we're writers we should, then we will soon find our world expanded through the beauty, struggle, and/or reality of another writer's work. One writer who does that for me is Tim O'Brien.

First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross carried letters from a girl named Martha, a junior at Mount Sebastian College in New Jersey. They were not love letters, but Lieutenant Cross was hoping, so he kept them folded in plastic at the bottom of his rucksack. In the late afternoon, after a day’s march, he would dig his foxhole, wash his hands under a canteen, unwrap the letters, hold them with the tips of his fingers, and spend the last hour of light pretending. As we read through Jimmy Cross' story, we see how he copes with the war through imaginings about the elusive Martha, who keeps pieces of his soul clean (notice how he cleans his hands before reading her letters) while the rest of him is "dirtied" by war. It is a painful and personal story that hits me in the feels every single time I read it. O'Brien's style is very direct, yet he buries the truth within his narration, circling ever closer to the true moment by recycling the story and its impact on every other character in the story.

I've written before about how this short story has on more than one occasion caused me to write about the things that I carry, the tangible and intangible. I carry a messenger bag and a laptop. I carry parental guilt and debilitating fear. What do you carry? They carried all they could bear, and then some, including a silent awe for the terrible power of the things they carried.”  Reading as a writer changes us, both as writers and readers. When I first started writing (but a decade before I was published), I would read and re-read my favorite author to try to get a feel for her rhythm in pacing, sentence length, paragraph length, and chapter length, but the reading and re-reading wasn't active enough, so I started typing out the first 3 chapters of her book to try to get a sense of her pacing at the opening of a novel. Since I'm a fast typist, I started to get an intuitive feel for her natural patterns. She was an historical writer, and at the time I thought that's where my interest lay, and it helped me in big ways and small. I still have a natural feel for chapter length, scene length, and how to start a book. What I was doing wasn't mimicry, but more like a painter who learns the brush strokes and techniques of a master painter before s/he is ready to paint her/his own masterpiece. When I went into my MFA program, we had to read and write a critical response on THREE books each month (for two years). At the time, I was so exhausted, I didn't see what I was learning until it was over, but it taught me to read critically and in such a way that it's hard to turn off. I honestly don't want to read every text critically. Sometimes, I want to shut off the writer-mode and enjoy a good book in the same way I enjoy Rom-Com and Action Adventure movies. I just want to enjoy them for what they are. They're not critically acclaimed think pieces, but they give me some much needed laughter and relief from life stresses. Years after I started the writing process, I finally acknowledged that I wasn't an historical writer. I wanted to be, and I still enjoy reading them, but I don't have the right voice and tone for historical, and it took years of trial and error to find my true genre home. I still read widely, as I did when I worked for the library, in nearly every genre (except horror...because I would never sleep if I did). When I've gone through several disappointing "new" books, I often turn to my favorite authors and re-read novels that I enjoyed, but when I'm reading them for the second time, that little writer voice in my head comes out and starts intruding on my reading time. I catch myself mentally editing, or noticing that particular writer's tic. And it dampens my reading pleasure. I've learned my writing craft--honed my writer's toolkit--by reading and re-reading books and passages, but when it comes time to simply read, I often have to find a new book so I can read purely for enjoyment. Eventually, I'll get around to thinking about the book as a writer, but sometimes, a writer simply needs to turn off the criticism and enjoy the book for what it is. In what ways has reading as a writer changed you as a writer? As a reader? And is that a good thing, or bad? Late post today as--after a full day of yucky chores getting the kids ready for back to school (what happened to starting after Labor Day?)--I headed to the gym. Not out of strong desire, but rather my son is on a M/W/F schedule, and I don't want to be "that mom" who drops and goes. So I go in. And if I go in, then I should probably, you know, work out.

Most of my life, I've had a love/hate relationship with running. I like it--after I've done it, but getting started is like pulling the cord on a lawnmower that's been sitting in the garage for 8 months. I know this about myself, so I always give myself a bailout. I start running, and after 15 minutes, if I really don't want to continue, I can bail. Typically, that 15 minutes is enough for some feel good hormones to kick in and I can finish the workout. I can't think of a single time when I started that 15 minutes and bailed, but that little white lie, "you can quit" gets me started every single time. I have to lie to myself for my own good. Writing is often like that. There are writing days when we really, really, really don't want to write. <fill in your favorite "reason" that today is a bad day to write> Life puts demands on our time. Kids, family, day job, spouse, pets, and all we really want is a dose of Netflix and a glass of wine. When those days happen, I give myself the same bailout opportunity. IF I start writing, and after 15 minutes I still want to binge watch Dexter, fine. But I have to write for the full 15 minutes first. And like running, once I start writing, the endorphins kick in and I keep going. I just need to lie to myself to get started. So when you have one of those days, <fill in your favorite "reason" that today is a bad day to write>, you only have to do one thing. You guessed it. Lie. Tell yourself that you only have to write for 15 minutes today. I'm guessing that once you start, you won't want to quit after 15 minutes. :) Is there a connection between our lives and the story we are writing? In an obvious sense yes. And no. Yes, of course it revolves around the writer's experience, but no, it is not a poorly disguised autobiography. I'm reading The Hidden Machinery by Margot Livesey, a gift from my MFA mentor. In the first essay, she discusses both Henry James and E.M. Forester. Forester, she claims, could have finished A Passage to India when he first started the book in 1913. The pieces were all in place, he had four novels under his belt, so he had the skills, but Forester was never happy with it. Until he was. Why did this novel take Forester longer? "He needed certain things to happen--a war, a massacre, the discovery of his own sexual nature and of how he too could be corrupted by the white man's power in India--before he knew where the [book] was going." --M. Livesey He had to mature, essentially, to the point where the novel made sense. He first had to experience the things which would became central to the story. The writer's life informs and reforms the writing. I could only write Untouchable after going through a hellish divorce. I have a novel in a drawer that languished, waiting for me to get over the hurdle at the first turning point. And since I didn't get through the barrier in my life, the character failed to thrive. "Both inner and outer events were required before he could write [the] novel." It's not just physical events, like Forester's return trip to India. It's internal change in the mind and spirit of the writer that impact the writing. I've written eight novels. Seven are published and they are the result of who I was and what I believed at the time they were written. But that one book that's not yet published makes me wonder. Where do I need to be, what do I need to experience, what must I observe before the book is ready for birth? What inner or outer events must take place before I feel satisfied with this book? And can I nudge those events into place faster so I can finish it already? I haven't gotten that far in Livesey's book, but I'm guessing that no, I can't shove myself into the fire to force the inspiration. Instead, I must keep writing and writing, putting in my time and wallowing in the characters, before those internal and external events converge. Short stories to develop a character for a novel? To bring about a serial? To reach readers?

Good idea or not? Writers, what say you? Writing has its ups and downs, and the downs seem a bit like torture and we fill our minds with doubts... I can't do this? Can I do this? I suck! said with emphasis when the words on the screen cannot match the images in our heads. That's when we need a friend like Sol LeWitt who wrote this wonderful letter to Eva Hess: You seem the same as always, and being you, hate every minute of it. Don’t! Learn to say “Fuck You” to the world once in a while. You have every right to. Just stop thinking, worrying, looking over your shoulder, wondering, doubting, fearing, hurting, hoping for some easy way out... Remember, before Nano started, when you decided to say NO to perfectionism? Now's a good time to banish that perfectionism and write crap for a day or two: If you fear, make it work for you — [write] your fear & anxiety. And stop worrying about big, deep things... You must practice being stupid, dumb, unthinking, empty. Then you will be able to If only someone would read us the full letter every day to remind us that writing isn't easy, but it's our choice, our calling, our special form of torment...and one that we really do love. Oh, wait, Benedict Cumberbatch did read this letter, and it's wonderful. And I'm serious. We should listen to it every day, so we remember to shut up the perfectionist editor in our heads and just write, or as LeWitt says, just do! The full text of the letter is here.

|

AuthorWriter, college professor, lover of story, fan of all things bookish. Plus chocolate, because who doesn't love chocolate. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed